Craig Stirrat: Class, inequality – the new normal or same old same old?

Craig Stirrat

Grampian Housing Association chief executive Craig Stirrat shares why a 1966 comedy sketch still speaks to Aberdeen in 2026.

Two years on from a national housing emergency being declared, Shelter Scotland has warned that homelessness in the country is becoming the “new normal” as figures showed 18,000 households are living in temporary accommodation – a 9% rise on the previous year.

When it comes to the headlines on affordable housing shortages what is often not mentioned is which communities (albeit the insecurity of the PRS is often portrayed as a major cause) are driving this homelessness crisis.

Current statistics reveal a major driver is single (largely male) person homelessness (representing 50% of all cases) because of breakdown in relationships (asked to leave = 47%) – and from which we can assume a large proportion came from social rented homes (the stats do not record the previous tenure occupied – other than if the household previously had their own social tenancy (10%) or supported accommodation (7%) =17%) albeit that the largest percentage of households in the PRS are single (38%).

If that’s not bad enough, despite improvements, most Scottish local authorities had higher child poverty rates in 2023-24 compared to a decade ago, making the 2030 target of less than 10% difficult to reach.

The new normal or same old same old?

In 1966 (the year England won the World Cup!), The Two Ronnie’s and John Cleese delivered one of British television’s most enduring pieces of social commentary. Their “Class Sketch” - a simple tableau of three men arranged by height - used humour to expose the rigid social hierarchy of the time. Cleese, towering above the others, announces: “I look down on him because I am upper class.” Ronnie Corbett, at the bottom of the trio, accepts his position with the resigned line: “I know my place.”

What made the sketch so powerful was not merely its wit, but its accuracy. It distilled the British class system into a visual metaphor so sharp that it has remained part of the national consciousness for six decades.

Yet the most striking thing about the sketch today is not how much has changed, but how much of its underlying truth remains.

Britain no longer talks about class in the language of bowler hats and clipped vowels. But the structures that shape people’s life chances—economic security, housing, education, and health—have not disappeared. They have simply become more complex, more spatial, and in many cases, more entrenched.

Where the sketch used physical height to illustrate hierarchy, modern Britain uses:

• income and wealth distribution

• postcode‑based disadvantage

• access to secure, affordable housing

• digital inclusion

• health outcomes and life expectancy

The lines are no longer spoken on a stage; they are lived in communities where opportunity is unevenly distributed and where the consequences of inequality are increasingly visible.

It is a sad indictment of successive government policy that the social rented sector accounts for 43% of all people in poverty in Scotland. In addition, the highest rates of fuel poverty are also found in the social rental sector, with 61% of local authority and 60% of housing association tenants estimated to be fuel poor, compared to 44% in the private rented sector.

So clearly whilst access to good quality affordable (mainly social) homes is necessary, it is not sufficient to tackle the deep-rooted deprivation in many of our existing communities – adversely affecting the life changes of the children who grow up in these communities.

Aberdeen – a tale of Two Cities: A Decline in Disposable Income

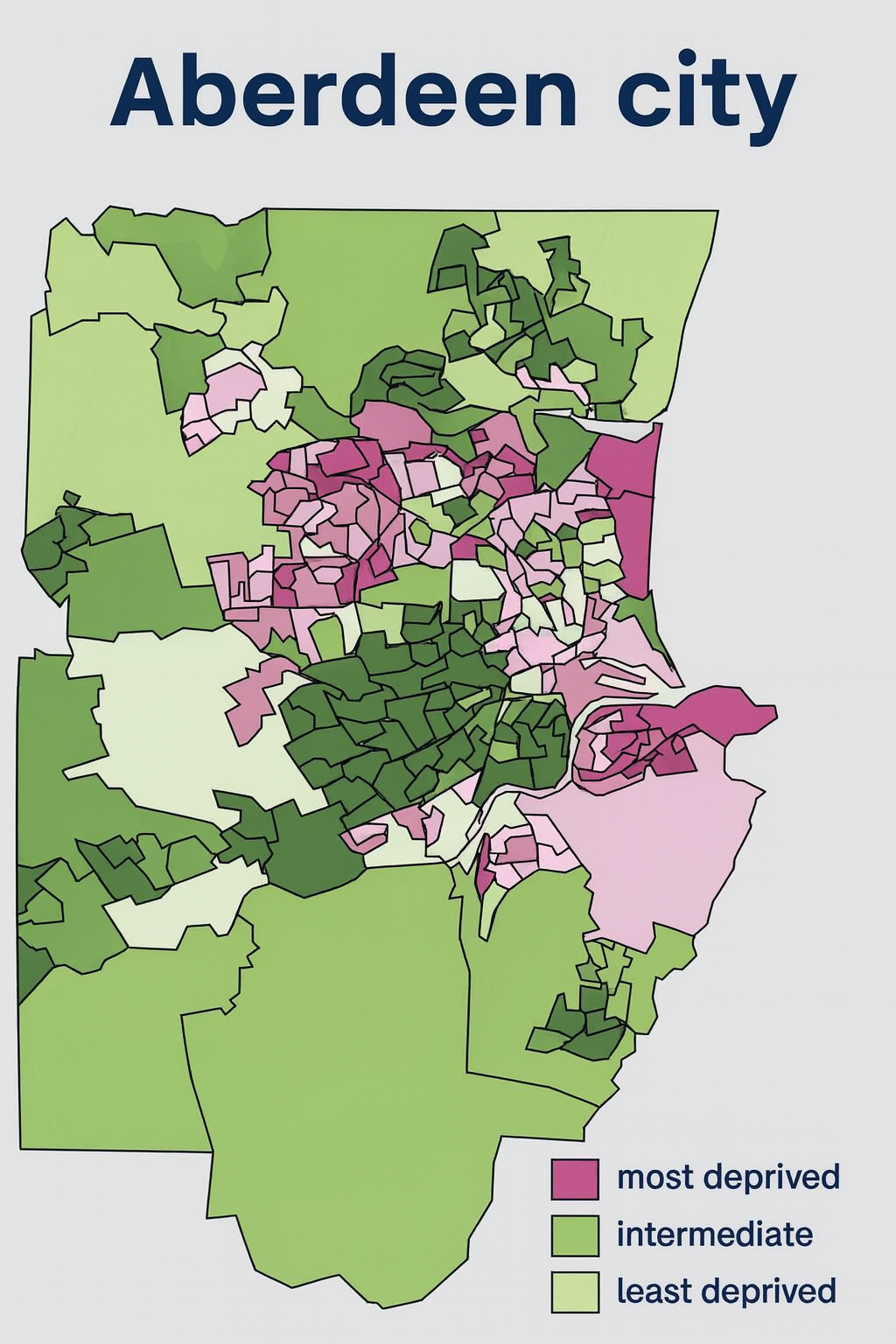

Take, for instance, Aberdeen, which has long been perceived as a prosperous city - an engine of the UK’s energy economy and a place where wages outpaced national averages. But the decade from 2013 to 2023 tells a more complicated story (see SIMD map showing entrenched deprivation in Aberdeen’s Council Housing Estates).

Recent economic analysis shows that disposable incomes in Aberdeen City declined over this period, bucking the trend seen in many other parts of the UK. This shift is not a technical anomaly; it reflects structural changes in the local economy, the volatility of the energy sector, and the rising cost of living.

A fall in disposable income has profound implications:

• Households have less financial resilience, making them more vulnerable to inflation, energy price shocks, and insecure employment.

• Housing affordability deteriorates, as rents and house prices continue to rise faster than wages.

• Demand for social housing increases, placing pressure on already stretched systems.

• Health outcomes worsen, particularly in communities already experiencing disadvantage.

Aberdeen’s story is not one of uniform decline. It is one of divergence—a widening gap between those who remain insulated by higher incomes and those whose living standards have eroded.

If the Cleese/Ronnie’s class sketch were rewritten today, the dialogue might not be about social status at all. It might be about life expectancy.

Across the UK, the link between socio‑economic status and health has become increasingly stark – adding further pressures on the NHS which is already struggling with an ageing population:

• People in the most affluent areas live significantly longer than those in the most deprived.

• Healthy life expectancy—the years lived without disabling illness—shows an even wider gap.

• Rates of chronic illness, mental health conditions, and early mortality are disproportionately concentrated in communities facing economic hardship.

These patterns are not accidental. They are the predictable outcomes of inequality.

In Aberdeen, areas of multiple deprivation experience higher rates of:

• cardiovascular disease

• respiratory illness

• diabetes

• substance misuse

• poor mental health

• premature death

The decline in disposable income only intensifies these pressures. When households must choose between heating and eating, or when insecure housing undermines stability, health becomes the first casualty.

Housing is the arena where economic inequality becomes most visible and tangible —and most consequential.

For those with higher incomes, housing remains a source of security and wealth accumulation. For those without, it is a source of stress, instability and helplessness – all which contribute to poor health and wellbeing outcomes.

Whilst I welcome the recent More Homes Scotland announcement, if the agency is to have a wider lasting legacy – it must ensure that in the drive to provide more affordable homes more quickly – it does not ignore the need for the regeneration of many existing (largely social rented) communities to tackle the entrenched inequalities, otherwise we will have failed to tackle some of the root causes of homelessness.

People do not have to “know their place” - if housing providers collaborate to help to build community pride, a sense of hopefulness and control over life chances.

In 1999, Tony Blair announced that “no-one is left behind, no-one excluded, “ and that we will “ halve child poverty in 10 years and abolish it in a generation.”…… and we all know where that ambition led us – a whole generation of the socially excluded and for many a revolving door of homelessness.

When it comes to future housing supply strategies we must - as Professor Duncan MacLennan advocates - engage with the widest group of stakeholders in reframing the housing issues and really understand the economic drivers in order to improve the housing system, by ensuring that creating better places is at the core of the More Homes Scotland agenda.

So, let’s not wait another 25 years for change – we have the opportunity to establish “the new normal” - if we make 2026 the year where all social housing providers draw the proverbial line in the sand of deprivation and build on the examples of many Scottish community-based housing associations.