Garrett Grainger: Celebrate pride month in Scotland by ending LGBT homelessness

Garrett Grainger

Garrett Grainger, research associate at the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE), discusses the steps that can be taken to help end LGBT homelessness.

Scotland has an ambitious plan to end homelessness. Local authorities in Scotland have a statutory duty to secure settled accommodation for homeless households. As a result, people who are at risk of becoming homeless in the near future or have become homeless can approach their council where they can get assessed for housing assistance in either the private or social rental market.

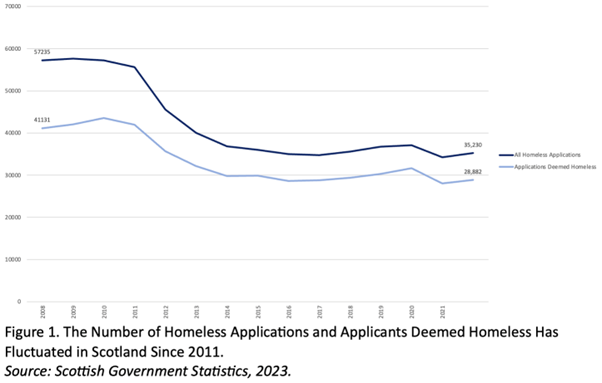

Figure 1 shows the number of homeless applications and applicants assessed to be homeless fell 2011–2017 before slightly rising again 2017–2020. During the COVID-19 pandemic, homeless applications and assessments briefly decreased; however, that trend has started to reverse now that the pandemic has ended.

This represents a 36.7% decrease in the number of people who submitted homeless applications, a 31.1% drop in the number of applicants who were assessed to be homeless, and a 14.1% increase in the proportion of homeless applicants who are deemed statutorily homeless. It is therefore undeniable that the Scottish Government and local authorities have made tremendous progress in addressing homelessness.

Figure 1 illustrates several trends that have partly been created by the Scottish Government. The sudden decrease in homeless applications 2011–2014 may reflect new policies that the Scottish Government has implemented. Around that time, local authorities started to offer homeless prevention services to stop constituents from entering the homeless system by keeping them housed.

The ‘priority need’ criterion, which had limited the duty to secure settled accommodation to certain households (i.e., families with children and vulnerable adults), was abolished in 2012. This policy extended the duty to secure settled accommodation and temporary accommodation to most homeless households. The shrinking gap between total number of homeless applicants and applicants deemed to be homeless correlates with the Scottish Government’s abolition of the priority need criterion.

Lastly, the recent dip and rise in homeless applications is attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, the Scottish Government instituted a nationwide eviction moratorium and allocated rental assistance to households at risk of homelessness. This helped stop people from entering the homeless system. Protections for renters relaxed as the pandemic ended. This coincided with increased demand for homeless assistance.

The “Ending Homelessness Together Action Plan” was published by the Scottish Government in 2020. It identifies five strategies—person-centred interventions, homelessness prevention, collaborative responses, rapid rehousing, and housing-led programmes—that local authorities should use to manage homelessness. This action plan specifies vulnerable groups—women, youth, single mothers, female victims of domestic violence, migrants without recourse to public funds, and racial/ethnic minorities—who have special needs that must be met to prevent or end their homelessness. Consequently, the homeless statistics published by the Scottish Government include information about age, sex, household composition, and ethnicity.

LGBT people are notably absent from the list of vulnerable subpopulations recognised by the Scottish Government. This is true even though an earlier draft of this plan published in 2018 recognised LGBT people as a legislative priority: “There is a legal duty for us to consider equality issues as we develop new policy and in particular the impact of the policy on people who share certain ‘protected characteristics’: age, disability, sex, gender reassignment, sexual orientation, race and religion or belief” (p. 40).

A potential reason for this neglect might be the lack of research on LGBT homelessness in Scotland. The national government and most service providers do not collect standardised data on LGBT homelessness in Scotland. Available estimates of LGBT homelessness in Scotland consequently come from UK-wide surveys. Fraser et al. (2019) estimates 25% of homeless persons in the UK are LGBT despite composing only 5% of the total population.

A few qualitative studies that were conducted in Scotland suggest LGBT people:

- Often become homeless in response to parental rejection, domestic abuse, and disapproving partners;

- Vary in their awareness of homeless services, avoid homeless service providers to protect themselves from discrimination, and/or hide their identity while getting resources from service providers.

- Resort to sofa surfing with supportive friends to stay sheltered while homeless.

- Think sensitivity training is needed to combat homophobia in homeless systems.

- Benefited from the Scottish Government abolishing priority need from its homeless system because it opened access to single applicants.

Although the Scottish Government suspended local connection tests in November 2022, they need to be permanently banned so homeless LGBTs are not discriminated against for migrating to large cities from rural communities where they are more likely to be accepted. LGBT people therefore confront unique pathways into and out of homelessness that require tailored interventions.

Despite their vulnerability, the Scottish Government neither mentioned LGBT people in its most recent action plan nor published data on LGBT homelessness in any of its annual reports. Although Scotland’s action plan explicitly aims to prevent homelessness in at-risk groups, this data gap prevents it from understanding the causes of and solutions to LGBT homelessness. Such institutional neglect will undoubtedly perpetuate LGBT homelessness.

Ignoring LGBT homelessness is problematic for three reasons:

- Being homeless exposes LGBT people to morbidity and mortality risks.

- Homelessness is extremely burdensome to public expenditures (Pleace and Culhane, 2016).

- The Scottish Government has a statutory duty under the Equalities Act 2010 to ensure LGBT people are not in/directly discriminated against by its homeless system

Policy recommendations

To fill this knowledge gap and end LGBT homelessness, we make the following policy recommendations:

- Revise national planning documents: The first step to fixing this problem is for the Scottish Government to explicitly define LGBT homelessness as a social problem in its action plan. This means adding LGBT people to the list of minorities it deems uniquely at-risk of homelessness, providing analyses of LGBT homelessness to its annual reports on homelessness, and allocating resources to areas where LGBT people are more likely to become homeless.

- Publish standardised data on LGBT homelessness: The latter point ties into the next set of policy recommendations. The Scottish Government is encouraged to collect and publish standardised data on LGBT homelessness in a publicly accessible format. This would enable social researchers and advocacy groups to understand the scope of LGBT homelessness, identify causes of LGBT homelessness for different groups, make substantive policy recommendations, and monitor the government’s progress on ending LGBT homelessness.

- Make intersectional data publicly available: Intersectionality is the simple idea that social identities overlap and interact to shape our life chances and experiences. This implies our experience of sexuality is moderated by our race, ethnicity, gender, class, age, and ability. If we take this logic a step further, we can start to think about ways the causes and experiences of LGBT homelessness vary across intersectional subcategories. Diverse interventions are therefore needed to end LGBT homelessness. The Scottish Government can facilitate these interventions by publishing intersectional data.

Release multi-scalar data. Multi-scalar data facilitates analysis at different geographic levels: national, regional, local authority, and postcode. Such data would allow researchers to trace fluctuations in LGBT homelessness, help elected officials and charity groups allocate resources where they are needed to end LGBT homelessness, and lobby councils to make their homeless system more inclusive for LGBT people. - Partner with social researchers and advocacy groups: Publishing better data needs to be coupled with research and advocacy. It has been long recognised that data do not speak for itself. Adequate theory and methods are needed to both produce data and make sense of observed homeless trends. Social researchers will therefore play a vital role in ending LGBT homelessness. Advocacy groups can then use those findings to promote legislation and policies that end LGBT homelessness.

- Analyse LGBT homelessness in reports published by Scottish Government: The Scottish Government publishes an annual report called “Homelessness in Scotland” and occasional Equalities Breakdown that have not mentioned LGBT homelessness. Including LGBT people in these reports is essential to understanding their housing needs and making effective interventions to end homelessness.