Ken Gibb: Scottish Government proposes changes to council tax but falls short on broader reform

Professor Ken Gibb

CaCHE director Professor Ken Gibb responds to the recent proposal to change the multipliers for higher band council tax properties to increase revenue for local government.

A joint paper by the Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) was released yesterday as part of the announcement about a short consultation process on changing the multipliers for higher band council tax properties to raise more revenue for local government, and repeating the process that occurred after the 2016 Scottish election (introduced in 2017). This is also an attempt to deliver more tax income in a fair way where the burden, during the cost of living crisis, falls on those who can bear it most.

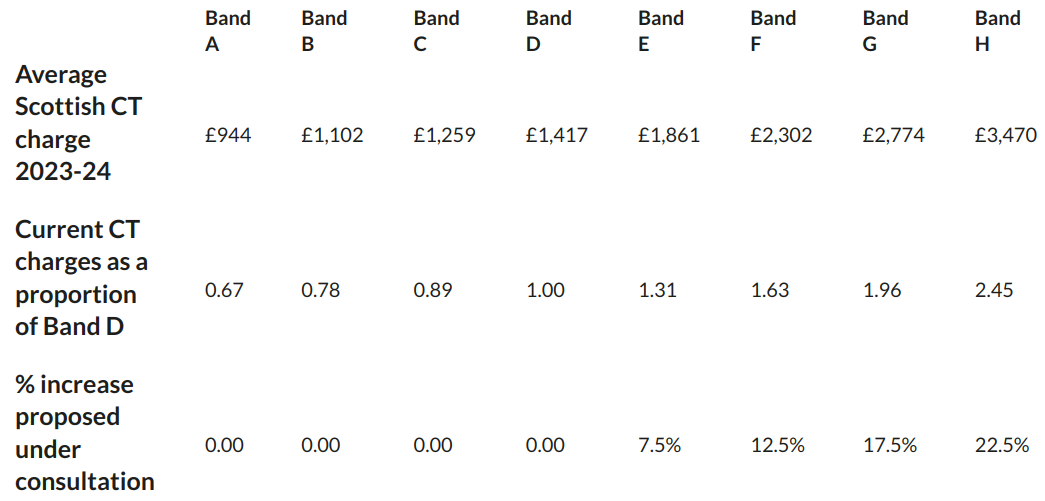

Specifically, the consultation, essentially binary (should we do X or not?), is to change the weights for bands E to H as follows:

The increase to the top four bands replicates the proportionate increases introduced in 2017. Consultation analysis suggests that this will impact 28% of properties (based on 2023-24 figures). The consultation indicates that this increase in the multipliers might be phased in over three years. The full increase implies a rising cost from £139 a year for Band E up to £781 for Band H.

The proposal discusses the Scottish council tax reduction (CTR) scheme, an income-related rebate system which takes 360,000 households (15%) out of paying council tax. This was modified in 2017 to protect low-income households in higher band properties affected by these multiplier changes and hence higher gross bills. Presumably, this continues with the consultation proposal.

The consultation paper does stress that council tax is regressive. It does acknowledge criticisms of the present system, e.g. gross payments as a proportion of income and the patent unfairness of the compressed relationship between CT payments and assessed property value (that is, Band H has a charge about three times that of Band A even though the value of Band H are on average about 15 times greater than those of Band A).

Tactically, this is a recurring approach from the Government. It has been done before with council tax, and it echoes changing the tax rates for Land Building Transactions Tax. And, like the rent freeze/rent cap from 2022, it is something that can be done. Politically, its proponents clearly hope that the CTR scheme, phasing in the reforms, and the focus on the top four assessed value bands – will blunt criticisms of the proposal. There is also no doubt that councils need more income to deliver essential public services.

My immediate response should be set in context. Since devolution, we have had several reviews and debates around reforming council tax:

- The Burt review for the Labour-lib Dem coalition proposed a capital value tax. This was killed off before it was even published but a very similar tax was successfully introduced and retained in Northern Ireland.

- The SNP minority government had a commitment to a tartan tax where the then ability to raise income tax by up to 3%, and would be used in place of council tax. This was dropped because it was infeasible and would not raise anything like enough funds.

- The Concordat between the Scottish Government and local government froze the council tax for nine years. While politically very popular (for obvious reasons), this hampered local government and disconnected local tax from local accountability.

- The Local Tax Commission (2014-15) proposed abolishing the council tax freeze and moving to a combined capital value or proportionate property tax and an element of local income tax. Party manifestos in 2016 drew up proposals for reform (including notably a shift away from local income taxes towards property and land value taxes). However, the incoming SNP minority government proposed the de minimis changes to the multipliers for Band E-H and the revisions to the CTR scheme.

Overall, a lot of activity but very little effective progress on much-needed council tax reform.

My initial response to the new consultation would be as follows.

First, this is a crude attempt to use the top half of the bands to raise more revenue and makes strong assumptions about the assessed value of the properties, the bands that they fall into (and whether these properties are in these bands if valued in current prices), and, the incomes and capacity to pay of households in different bands (it is not just about CTR). To remind everyone – council tax is based on 1991 assessed values. A key point of critiques of the system is that it is, with every year, more and more detached from the reality of housing markets and the distribution of real value. The local tax commission was just one voice among many arguing for a general and regular periodic revaluation; something made much easier by advances in property technology, automatic valuation, etc.

As an aside, a striking point in Peter Apps’ recent book on Grenfell is the fact that the UK is only one of two countries that allows multi-storey buildings to be constructed with just one staircase. In the same way, the UK is one of only two countries with a banded property tax – there is good reason why others do not follow. And it is widely recognised that there must be regular general revaluations to keep property tax systems credible. The Welsh have managed to do this – why not Scotland?

Second, the consultation proposal is a pragmatic device, but it does nothing to address the wider structural problems with local government finance nor with how we do property taxes. Housing to 2040 sees better property taxes as a key way to manage housing markets toward more stable outcomes, calling initially for a review of devolved property taxes (LBTT and CT). But there is nothing here to suggest that structural reform – moving to a more progressive and efficient model of property taxation – is being considered. This is a part of the agenda of our current research project on housing policy development funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Third, I would argue that local government finance reform needs to be nested in reform of local government powers and boundaries. Reform needs to be systemic and inclusive. Tinkering with one aspect does not begin to deal with the wicked problems of reforming local government in Scotland.

CaCHE will respond more fully to the consultation, which closes on 20 September.

This article was originally published on the CaCHE website